- Original Article

- Open access

- Published:

Corporate social responsibility and accountability: a new theoretical foundation for regulating CSR

International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility volume 5, Article number: 2 (2020)

Abstract

The absence of consensus on what should constitute Corporate Social Responsibility has inhibited consistent CSR legislation around the world. This paper poses a fundamental question on what should constitute CSR and what should be the nature of CSR regulation? By constructing the boundaries of CSR, the paper offers scope for consistently developing CSR regulation around the world. It construes CSR as consisting of business relation and impact relation, and demonstrates that these are intertwined with legal responsibilities of business and, consequentially, with accountability. It accomplishes this by establishing the obligatory nature of responsibilities using the lens of ethical and legal jurisprudence. This new approach towards CSR recasts it as an obligatory responsibility that is linked to accountability. Furthermore, the framework provides a foundation for consistent development of CSR regulation across different countries that can lead to effective discharge of corporates’ social responsibilities.

Maintext

A vast literature has focused on the nature, role and the dynamics of corporate social responsibility. More recently, an emerging body of literature is examining the need for regulating CSR and the role of law (Abah, 2016; Amao, 2013; Buhmann, 2006; Buhmann, 2011; Dentchev, Haezendonck, & van Balen, 2017; Idemudia & Kwakyewah, 2018; Malesky & Taussig, 2017; Malesky & Taussig, 2019; Nieto, 2005; Okoye, 2016; Osuji, 2011; Osuji, 2015; Situ, Tilt, & Seet, 2018; Thirarungrueang, 2013). However, imposition of regulation on corporates for CSR faces several challenges in the absence of consensus on the nature of obligations that businesses have under current CSR models. This paper theorises the conceptual underpinnings of responsibility and its relationship with accountability to develop a formal model to underscore the nexus between CSR and corporate accountability while providing a novel theoretical foundation for regulating CSR. In the process, the paper constructs boundaries for CSR to enable an appropriate regulatory framework to be put in place.

This paper examines the nature of corporates’ social responsibilities, and their relationship with legal responsibilities to establish a framework for corporate accountability. In particular, the paper attempts to answer the following research questions. Firstly, should CSR be within the realm of voluntarism or does it consist of mandatory obligations? Using the legal theory on morality, the paper underscores the relationship between legal and moral responsibilities to draw a parallel link between economic goals of firms and CSR to demonstrate that CSR obligations are intertwined with legal responsibilities of business. As these responsibilities are connected with accountability, the paper demonstrates that the true nature of CSR is obligatory and not voluntary. In the process, the paper provides a formal model for regulating CSR that can effectively ensure fulfilment of corporates’ social responsibilities. The second question the paper examines is what should be the nature of CSR regulation? In particular, what conditions should CSR regulation satisfy for it to be effective in ensuring that corporates discharge their social obligations? Here, the paper sheds light on the nature of optimal CSR regulation by concretising the exact nature of social obligations that corporates have to focus on for their CSR.

Although CSR scholarship is highly influenced by Carroll’s CSR pyramid (Baden, 2016; Carroll, 1979; Carroll, 1991; Carroll, 1999; Carroll, 2016; Lee, 2008; Visser, 2006; Wood, 2010), it is greatly fragmented (Aguinis & Glavas, 2012). The varied conceptualisations of CSR have lent a broad scope to CSR (Carroll, 1999; Waddock, 2004; Aguinis & Glavas, 2012). For instance, Carroll’s conception includes philanthropic contributions by corporations. Such elements have greatly diluted the scope for introducing regulation within CSR. They gave opportunities to firms to exploit such philanthropic contributions to do more harm subsequently (Luo, Kaul, & Seo, 2018). In cases where CSR regulation was brought in, Carroll’s highly influential theory may have contributed to laws that are not necessarily most effective in protecting stakeholder interests. As one example, the Indian government has mandated CSR requiring corporates to spend a proportion of their profit on social projects (Chhaparia & Jha, 2018; Gatti, Vishwanath, Seele, & Cottier, 2019).Footnote 1 Indian corporates can claim to have discharged their CSR obligations through such philanthropic spending while not adequately addressing the immediate concerns relating to stakeholders (Singh, Holvoet, & Pandey, 2018; Subramaniam, Kansal, & Babu, 2017). Carroll’s model has contributed to a wide scope and ambit of CSR that has significantly diluted the scope for regulation with the potential to lead to misplaced regulation.

In contrast to Carroll’s approach, we define responsibilities as those that arise while discharging the primary functions associated with a role. These primary functions that intrinsically come with a role are associated with two sets of responsibilities—legal and moral. For example, in case of firms, these legal responsibilities include a wide gamut of economic and legal activities that firms are involved with to discharge their primary function of conducting business. While pursuing such activities, a range of moral responsibilities concurrently arise. We develop the concepts of business relation and impact relation in this paper to encompass these moral responsibilities. The paper suggests that CSR should be within the boundaries of these moral responsibilities that are in the form of business relation and impact relation. This way we identify legal responsibilities and the corresponding moral responsibilities in a more concreate fashion enabling a framework for CSR regulation to be put in place.Footnote 2

CSR has for most part remained voluntary (Carroll and Shabana, 2010; Aguinis & Glavas 2012; Dentchev et al. 2015; Dentchev et al. 2017; Lamarche & Bodet, 2018; Agudelo et al. 2019) and relied on self-regulation through codes of conduct with the decision to comply with the codes of conduct firmly within the forte of corporations (Bondy et al. 2008). It allows corporations flexible implementation and evaluation of the codes of conduct based on their choices (Bondy et al. 2008). The vast literature on the purpose, role and nature of a company and its management is ambivalent on the obligations of businesses towards CSR although it acknowledges that the ‘corporation has the onus of responsibility to sustain relationships with all stakeholders, in particular with stakeholders who are claiming adverse social and other impacts’ (Ross 2017). As Dentchev et al. (2017) suggest, some scholars emphasize that managers of a company have duties towards the stakeholders as they are agents of the company but they do not go beyond that point. Consequently, CSR lacks legal accountability for non-performance of social obligations by companies. This has steered CSR as a tool to advance strategic interests than as a required obligation for a company (Carroll and Shabana 2010; Shiu & Yang, 2017; Lamarche & Bodet, 2018).

A compelling development in the quest for accountability is the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) framework proposed by Elkington (1994). The TBL framework focuses on examining a company’s societal, environmental and economic impacts (Elkington, 1994; Elkington, 1997). However, as Adams et al. (2004) suggest, the increased volume of disclosure has not improved the “quality or the level of accountability discharged”. The absence of comprehensive mandatory requirements for TBL accounting and reporting has weakened the system for the discharge of social obligations by the companies (Adams, 2004).

The extant scholarship has examined if law has any role in the CSR (Amao, 2013). The increasing number of negative externalities of corporate activities and the minimal role that voluntary approaches to CSR have played in mitigating these, have motivated scholars to explore the link between law and CSR (Okoye, 2016). ‘In the event of conflict or serious harm to the environment, animals or people, where corporate irresponsibility is occurring, it is manifestly illogical to leave to the corporation the task of self-regulating’ (Ross 2017). The discussions on CSR and its relation with law are beginning to focus on the need for regulating CSR (Okoye, 2016). However, clarity on the role and nature of obligations under CSR in the functions of business continues to evade these discussions posing significant challenges for designing a framework for CSR regulation.

This paper makes several compelling contributions to the extant scholarship on CSR and the regulation of CSR. It makes a substantial contribution to the debate in the field of CSR by developing the link between CSR and accountability. Firstly, the paper establishes that CSR should be a mandatory obligation and not a voluntary construct. It develops a novel theoretical framework to underscore how moral responsibilities arise concurrently along with legal responsibilities when discharging the primary functions, with fulfilment of both forms of these responsibilities becoming obligatory through accountability. It uses this framework to bring accountability to the CSR literature that has otherwise remained in the realms of voluntarism. Secondly, it defines boundaries for CSR, and provides a basis for determining the social responsibilities for which corporates have to be held accountable through regulation. Thirdly, it provides a framework for regulating CSR while clarifying the fundamental nature of what should constitute CSR regulation. It bridges a glaring gap in the literature with regard to linking social responsibilities and accountability by providing a framework that can be instrumental in developing CSR regulation. Fourthly, it overcomes a severe limitation posed by the existing broad conception of CSR that has significantly restricted the scope for regulation by proposing an alternate framework for CSR that more closely links CSR with moral responsibilities arising along with legal responsibilities when an organisation is discharging its primary functions. Thus, the paper makes fundamental contributions to CSR theory and the theory of CSR regulation.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. The following section discusses voluntarism in CSR, the effects of ignoring accountability in CSR frameworks, and the need for CSR regulation. The third section develops the new CSR regulation framework. It provides the theoretical basis for linking responsibility and accountability. It classifies responsibilities as legal and moral responsibilities. Using the lens of ethics and legal jurisprudence, it demonstrates that there is a mutual relationship between legal and moral responsibilities and accountability. Furthermore, it examines this responsibility-accountability nexus in the corporate context to develop a formal framework linking CSR to corporate accountability to provide a theoretical basis for regulating CSR. The final section concludes the paper summarising the significance of the new CSR regulation framework that can lead to effective fulfilment of CSR obligations by firms.

Voluntarism and the effects of ignoring accountability in CSR

CSR is a well-established and highly evolved body of knowledge that has explored issues of trust, rights and responsibilities, and decision-making (Aguinis & Glavas, 2012; Jenkins, 2005). Beginning from early fifties, a large body of literature has examined CSR in both developed and developing countries (Bowen & Johnson, 1953; Davis, 1960; Friedman, 1970; Levitt, 1958; Davis, 1973; Freeman 1984; Drucker, 1984; Freeman, 2010; Carroll, 2016; Meynhardt & Gomez, 2019; Panda, D'Souza, & Blankson, 2019). McWilliams and Siegel (2001) define Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) as ‘actions that appear to further some social good, beyond the interests of the firm and that which is required by law.’ Matten and Moon (2008) suggest that CSR involves policies and practices of firms that indicate their commitment to wider society. Aguinis (2011) defines CSR as ‘context-specific organizational actions and policies that take into account stakeholders’ expectations and the triple bottom line of economic, social, and environmental performance.’

Sachs, Rühli, and Kern (2009) suggest that CSR has roots in morality and underscore corporates’ responsibility to not harm society and environment while positively contributing to the welfare of society and its stakeholders. Thus, following the principles of ethics, corporates should not disregard their social responsibilities while pursuing their economic goals (Baden, 2016; Sachs et al., 2009), and is essential for firms to consider ‘environmental and social imperatives’ along with the economic considerations (Keith, 2010). As Carroll (2016) suggests, ‘Business is expected to operate in an ethical fashion. This means that business has the expectation and obligation, that it will do what is right, just, fair and to avoid or minimise harm to all the stakeholders with whom it interacts’.

Concepts of corporate citizenship, sustainability, and stakeholder interests are used to demonstrate the need for social responsibility of corporates. Dahlsrud (2008) examined 37 definitions of CSR, and suggests that the most common element of it is the acknowledgement of business having responsibility towards society or community while engaging in socially benefitting activities. CSR literature has widely acknowledged that corporates and society are interlinked, and that corporates must act for the benefit of society.

However, the lack of clarity, direction, and voluntarism have led to random picking of free choices of responsibilities rather than targeting community needs (Okoye, 2009; Okoye 2016). To cite a few cases, some corporates contribute to HIV services, some to environment and others to community work based on their individual preferences (Freeman & Hasnaoui, 2011) while ignoring the immediate adverse impacts of their production processes on environment or their corporate practices on employees’ health. Furthermore, under current CSR practices, companies benefit by mere propagation regarding their CSR activities without actual compliance (Vos, 2009). They may easily avoid social responsibility if they see no benefit or ‘business case’ or incorporate only those aspects that benefit their corporation (Barnett, 2016). In the current context, social responsibility is self-enforcing, has no sanction, and no enforcement (McInerney, 2007). Thus, the absence of clarity on social obligations of corporations has led to voluntary initiatives to meet obligatory responsibilities. Often, this voluntarism leads to core required obligations being considered as mere instruments for serving businesses resulting in misleading perception of responsibility while raising questions on the effectiveness of CSR practices.

Voluntary codes of conduct have been adopted by some corporates. As noted by Sobczak (2006), these codes have some legal force and can be enforced by the courts. However, as these codes are voluntary, the choice of adopting a code of conduct depends on the free choice of corporates. Furthermore, the framing of the content in the codes is dependent on the will of corporates in the absence of specific guidelines. For these reasons, corporates may adopt codes according to their whims rather than the minimal requirements, and they may have CSR codes that are not necessarily indicative of actual CSR practice (Bondy et al., 2008).

Voluntarism has also paved the way for companies to propagate CSR practices for strategic interests while blatantly violating human rights. For example, Volkswagen has a long list of reported CSR practices but the recent scandal over diesel emissions reveals how corporates disguise themselves as good businesses under voluntarism. The Rana plaza incident and the Coca-Cola case demonstrate the weakness of voluntarism, and draw attention to expedient need to address the existing gaps through a systematic approach.

The voluntary status accorded to CSR has impeded companies from taking proactive measures towards CSR. Several initiatives were taken by international organizations to make CSR more effective. Some of the major developments include the United Nations Global Compact, Global Reporting, Transnational’s Draft Code, and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) guidelines amongst others. The Global Compact provides a common platform for companies to report their CSR related policies and practices. It embeds many of the normative debates into its ambit (Berliner & Prakash, 2012) to make corporates more proactive in accepting their social responsibilities (Schembera, 2018). However, it is rooted in voluntary reporting that depends on the initiatives of the participating corporations. Berliner and Prakash (2012) point out the observations of Compact’s 2008 Annual Review indicating that ‘not all Global Compact principles are covered with the same level of detail,’ that ‘there is a wide disparity with regard to information available per principle,’ and that ‘reported information is not comprehensive, communications on progress focusing more on commitments and management systems than on materiality, performance and achievements’. Even the recent report submitted by corporations on Global Compact suggests that the situation has more or less remained the same till date. Unwittingly, the Global Compact has facilitated the process of corporations using it for ‘propaganda and logos of the initiative without having to comply with their commitments, or truly strive to improve their human rights records’ (Rivera, 2013). It lacks a proper monitoring mechanism and therefore, it is difficult to say if all the reporting corporations are actually implementing their CSR policies as reported.

OECD provides mere guidelines for responsible business conduct but does not have a mechanism to verify if corporates adhere to those guidelines. Global Reporting Initiatives (GRI) were introduced as set of guidelines for producing voluntary sustainability reports worldwide on economic, environmental and social performance by businesses. These guidelines remain within the ambit of voluntarism having no force of law and, thus, have similar limitations like the Global Compact for CSR practices. GRI was criticized for its focus on quantity than quality and could not achieve its goals (Vigneau, Humphreys, & Moon, 2015). Parsa, et al. (2018) suggest that even the disclosures under the requirements of Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) were motivated by Transnational Corporations (TNCs) need for enhancing their legitimacy. The wide range of disparities among corporations in their reporting has led to the movement towards integrated reporting (Eccles & Krzus, 2010, 2014; Eccles, Krzus, & Ribot, 2015; Eccles, Krzus, & Solano, 2019). The main purpose of integrated reporting “is to explain to providers of financial capital how an organization creates value over time” (IIRC, 2013). However, even these integrated reporting requirements are in the voluntary domain.

The tremendous shift of economic power towards dominant MNCs coupled with states’ weaknesses to regulate has significantly compounded the problem of missing corporate accountability in the face of voluntarism. McInerney (2007) suggests that voluntary approaches to promote corporate compliance with norms is not sufficient to protect citizens while a ‘structure is needed for corporates to be accountable’. Without accountability, responsibilities take the shape of mere voluntary practices that in turn dilute the obligatory nature of responsibilities to voluntary choices or subsequent delegation of core responsibilities.

The Triple Bottom Line (TBL) framework suggests that company performance on sustainability goals should be measured based on the value added by company’s societal, environmental and economic dimensions. The framework emerged as a response to the calls for corporate accountability (Elkington, 1998a). As Elkington (2018) states the framework “was supposed to offer a radical new way forward” with businesses going beyond their focus on profits to “improving the lives of people and the health of the planet.” It became a widely used tool to measure companies’ CSR activities, and offers partnerships between firms as a potential solution for transitioning into sustainability (Elkington, 1998b). However, there are several emerging critical views on the effectiveness of the TBL paradigm. As Norman and MacDonald (2004) assert, the TBL paradigm may “provide a smokescreen behind which firms can avoid truly effective social and environmental reporting and performance”. Elkington (2018) recalled his TBL framework 25 years after introducing the concept, stating that “this radical goal has been largely forgotten, and “triple bottom line” thinking has been reduced to a mere accounting tool, a way of balancing tradeoffs instead of actually doing things differently”.

Schrempf-Stirling and Wettstein (2017) observe that the corporates learn their lessons once litigations are filed against them and term it as ‘education function of human rights’. They assert that companies take active measures in documenting their human rights policy and CSR policies immediately after litigations for human rights abuses are filed against them. They suggest that this influences other companies in framing CSR and human rights policies for their businesses. Under the current CSR regime, companies need not have any mechanisms or policies for acting more responsibly. They have complete autonomy until they are prosecuted for violation of rights. A pertinent question here is whether society can afford to wait for a change in how corporations function with respect to CSR until negative impacts become evident? Furthermore, the process of other companies getting influenced by observing litigations of violating corporations to adopt appropriate CSR policies cannot be a universally standardised mechanism for corporate accountability. The social role and function of corporations together with their power and capacity provide strong reasons for recognising their obligations to society. This can be achieved by looking at CSR through regulation. Thus, there is a compelling need to have a proper framework of regulatory policies for companies to minimise their adverse impacts on society.

Furthermore, although CSR has mostly been a voluntary construct in scholarly discourse, market forces, non-governmental organisations (Alamgir & Banerjee, 2019) and institutions (Demirbag, Wood, Makhmadshoev, & Rymkevich, 2017; Zuo, Schwartz, & Wu, 2017) may compel corporates to act in a socially responsible manner. For example, consumers may refuse to buy the products or services of a firm that is known be producing them unethically or if they have “green skepticism” (Leonidou and Skarmeas 2017). While appropriate regulation is necessary to ensure that corporates’ social responsibilities are effectively fulfilled, these institutions may encourage firms to act responsibly. However, market forces cannot be relied upon for accountability (Wright & Nyberg, 2017) because there may not adequately protect stakeholders’ interests in the face of information asymmetry or when such institutions are not sufficiently developed. Hence appropriate regulation is required for CSR to be effectively discharged.

The absence of regulation poses significant challenges for corporates to realize and implement their CSR obligations. Voluntarism has led to blurred conceptions of the extent of social responsibility of corporations. As Osuji (2011) suggests, the ‘lack of regulatory intervention had led to stultification of independent development of CSR by trying social issues to financial performance’. For these reasons, several scholars see CSR in its present form as having major flaws. As Aaronson (2005) suggests, ‘responsible corporate behavior in the developing world is an issue that cannot be left to the voluntary discretion of business people but needs to be addressed by more stringent regulation’ and therefore, ‘legally mandated accountability is where attention should really be focused’. An emerging body of scholarship seeks to establish the need for regulating CSR for corporate accountability (Abah, 2016; Amao, 2013; Buhmann, 2011; Okoye, 2016; Osuji, 2011; Osuji, 2015; Thirarungrueang, 2013). As Osuji (2011) suggests ‘regulation is neither incompatible nor irreconcilable with ethical CSR’. This literature suggests that in the absence of regulation, CSR may not be implemented by firms while stakeholders may be vulnerable to the negative externalities arising from irresponsible activities of firms.

These emerging voices on CSR regulation may have encouraged some countries to formally legislate CSR obligations, as in case of India’s mandatory CSR Law (Companies Act 2013), France legislating compulsory sustainable reporting for public listed companies (Chauvey, Giordano-Spring, Cho, & Patten, 2015), EU mandating non-financial disclosures (Szabó and Sørensen 2015) or regulating CSR through its policy based approach or by identifying the regulatory opportunities through international human rights law (Buhmann, 2011), and context dependent measures in UK and US (Knudsen, 2018). However, these approaches to CSR regulation have several limitations. For example, India’s mandatory CSR law does not address the concerns of immediate stakeholders while corporates can treat CSR as a charitable activity while not explicitly stating it to be so (Singh et al., 2018; Subramaniam et al., 2017). In case of France, the goal of achieving increased transparency remains unfulfilled (Chauvey et al., 2015).

Furthermore, lack of conceptual clarity on the optimal nature of such regulation poses significant challenges in framing such legislation. Given the wide scope of how CSR is defined, regulation can be ad-hoc and ineffective in protecting immediate interests of stakeholders while firms get away with window dressing (Jamali, Lund-Thomsen, & Khara, 2017) or greenwashing (Alves, 2009). In light of these issues, we develop a new framework to demonstrate CSR as an obligation related to the primary functions of business as well as to its causal impacts, particularly with regard to endangering the rights of others and unjustifiably getting benefitted while pursuing their primary functions. This new framework underpins the need for accountability through CSR regulation.

A new framework for regulating CSR

We propose that going into the foundations of responsibility and its link with accountability using the legal theory of morality can provide a solid basis for underscoring the obligatory nature of CSR, and determining the nature of optimal CSR regulation.

Legal and moral responsibilities

Responsibility is an obligation and a duty to perform what is one supposed to do. Such an obligation may be ineffectively effected if it does not come with accountability for its non-performance or breach. Responsibility is important in the context of law and accountability. Barry and Shaw (1979) has defined responsibility as ‘a sphere of duty or obligation assigned to a person by the nature of that person’s position, function, or work’. In this sense, responsibility includes obligations associated with a job or function in addition to the primary functions of a role. Thus, as part of responsibility, moral obligations may be related to functional obligations of a role (Bivins, 2006). Consequently, moral responsibility ‘refers to the multiple facets of that function--both processes and outcomes (and the consequences of the acts performed as part of that bundle of obligations)’ (Bivins 2006). As Jansen (2013) suggests, responsibility includes whatever is required under law as well as whatever is morally indispensable. According to him, there is a moral responsibility to act in a manner that prevents unjustifiably getting befitted by endangering the rights of others (even if such acts are not illegal per se). This empowers victims of wrongs to obtain redress from wrong doers while getting justice (Goldberg & Zipursky, 2006). For these reasons, there is responsibility towards obligations to safeguard the rights of others. Such responsibilities are often linked to tort laws and principles of corrective justice.

As one example, a contractor who is assigned a contract to build a bridge has the responsibility of constructing the bridge to meet the legal requirements under the contract. This primary function of the role is a legal responsibility imposed upon the contractor. A breach or non-performance of this legal responsibility invokes provisions of accountability. However, in addition to this legal responsibility, the contractor has a moral responsibility to ensure that the people in the vicinity are not adversely impacted during the process of the construction of the bridge, and that workers are safe. These are moral obligations that are closely related to the primary functions of the contractor’s role. These moral obligations arise concurrently with the legal obligations that are associated with the discharge of the primary functions.

Primary functions are associated with a bundle of responsibilities. While some of these responsibilities have legal sanction and backing, others may not have such a backing but have intrinsic moral foundations and arise concurrently during the discharge of the primary functions. Thus, these latter responsibilities are closely intertwined with the legal responsibilities that are associated with the primary functions. As Green (2008) suggests, “.. where there is a union of primary and secondary rules—that is to say, wherever there is law—new moral risks emerge as a matter of necessity.” For example, if the contractor has a factory, it is her responsibility to ensure that the factory has a decent working environment so that the employee’s rights related to their working lives are not adversely impacted. This moral responsibility arises naturally and concurrently with the legal responsibility associated with the primary function of production. In such cases, the intertwined nature of the naturally arising moral obligations that are associated with legal responsibilities, and the inherent relationship of legal responsibilities with accountability suggests that accountability has to be linked with moral responsibilities for the bundle of responsibilities to be fulfilled. As Lord Devlin (1965) suggested, “Society may use the law to preserve morality in the same way it uses it to safeguard anything else if it is essential to its existence.” The approach developed here is consistent with Devlin’s theory linking morality with law (Dworkin 1966, Dworkin, 1998).

Moral responsibility has a broad scope. In particular, as Eabrasu (2012) suggests, moral pluralism and the inherent complexity in deciding what is moral or immoral complicates the assessment of the morality of various sets of products, services or industries. This broad scope of moral responsibility makes it difficult to define enforcement channels or provide a structure for its fulfilment. However, in this paper, we are concerned with moral responsibilities that are closely intertwined with legal responsibilities that are associated with the discharge of the primary functions of a role. It is for these moral responsibilities that accountability is equally related because of them arising concurrently with legal responsibilities when discharging the primary functions of a role.

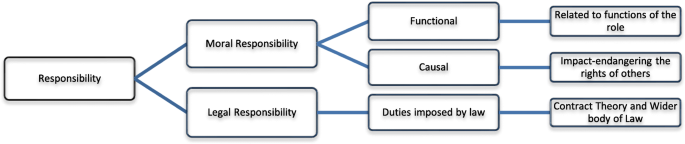

Figure 1 presents the legal and moral aspects of responsibility. The primary functions assigned to a role are associated with legal responsibilities. Registrations for the purpose of doing business, selling goods or services, meeting requirements under the law for performing the assigned role are legal responsibilities. They are rooted in duties imposed by law as well as from obligations that emerge from the terms of contractual engagements. These obligations come with the primary functions of a role. Here, parties are answerable for breach of their legal duties. However, moral responsibility entails moral obligations that relate to the primary functions of a role and the potential impacts of these functions. These moral obligations are intertwined with legal responsibilities associated with the discharge of the primary functions of a role. Thus, they are not purely rooted in morality or ethics but are closely intertwined with legal responsibilities associated with the primary functions.

Legal and moral responsibilities are related to each other, mainly, through three channels. Firstly, through the duties relating to the functions of a role. Both legal and moral responsibilities relate to each other for discharging responsibilities of the functions of a role. Legal responsibility involves discharging obligations that are primary functions of a role and moral responsibility involves discharging obligations that are associated functions of the role. Secondly, legal responsibility is related to moral responsibility as both seek to assume obligations against unjustified enrichment by infringing the rights of others. Hence, moral and legal responsibilities are related to causation -- the impact that a given function entails. Both legal and moral responsibilities have the obligation to refrain from causing harm while proactively engaging in the protection of rights of stakeholders. Thirdly, legal rules emerge principally from moral compulsions and needs. Legal responsibilities are associated with primary functions of business whose discharge involves interaction with legal rules. Thus, moral and legal responsibilities are interconnected as they are intertwined with the functions that are obligated to them by their role. These obligations together form the bundle of obligations under the functions of a role. For these reasons, legal and moral responsibilities must be considered together for effective discharge of functions.

Accountability

Accountability is ‘a moral or institutional relation in which entitlements are accorded to one agent (or group of agents) to question, direct, sanction or constrain the exercise of power by another’ (Macdonald, 2014). In the absence of accountability, there is no mechanism to question irresponsible behaviour and the actors are not answerable for their actions. Hence, accountability is a necessary element for an effective discharge of functions. Frink and Klimoski (1998) define accountability as ‘perceived need to justify or defend a decision or action to some audience(s) which has potential reward and sanctions power, and where such rewards and sanctions are perceived as contingent on accountability conditions’. Accountability, thus, keeps a check on the actions of the actors who have the responsibility or obligation to discharge their functions under a role.

Legal responsibilities come with accountability. An actor may be held liable for the breach of a duty or non-performance of a duty that he is obligated to do under the law. Moral responsibility considers that individuals are rational and can be held accountable for their actions (Barrett, 2004; Bivins 2006) as ‘moral agency entails responsibility, in that autonomous rational agents are in principle capable of responding to moral reasons, accountability is a necessary feature of morality’ (Barrett, 2004). As Bivins (2006) suggests, to ‘be accountable- one should be functionally and/or morally responsible for an action, some harm occurred due to that action, and the responsible person had no legitimate excuse for the action’. For these reasons, legal and moral responsibilities are closely connected to accountability in the context of a meaningful discharge of functions.

Dhiman, Sen, and Bhardwaj (2018) suggest that for social norms that are ought in nature, self-accountability will regulate individual’s behaviour in the absence of external accountability conditions. Likewise, for moral responsibility that is ought in nature, self-accountability will regulate behaviour in the absence of external accountability conditions. In particular, this can be seen in the context of missing tort law. In the presence of a developed tort law system, accountability assumes direct significance for moral responsibility. However, in case of self-accountability, individuals confronted with the expectations of assuming responsibility may simply reject the idea of responsibility itself while asking a simple question: ‘why answer?’ (Jansen, 2013). For these reasons, accountability having the force of law is required to fulfil reasonable expectations of responsibilities. Furthermore, accountability by itself has no value in the absence of expected responsibilities.

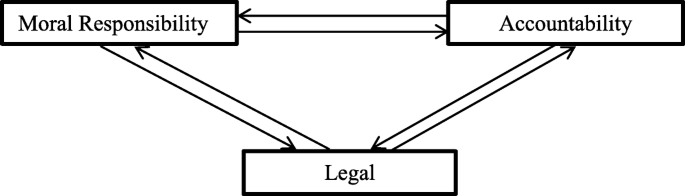

Figure 2 shows the inter relationship between moral responsibility, legal responsibility and accountability. As discussed earlier, moral responsibility is related to legal responsibility through its immediate relation with the primary functions of a role. Both legal and moral responsibilities give rise to the obligations of not endangering the legal rights of others and unjustifiably getting benefitted as both have an intertwined relation with ethics. This makes moral obligations ought in nature because of their immediate relation with legal responsibilities. Furthermore, legal responsibility seeks accountability by rooting responsibility in contracts and wider body of law while moral responsibility, through its immediate connection with the functional and causal aspects associated with the discharge of primary functions, seeks either self-accountability or accountability under torts. Thus, both moral and legal responsibilities are incomplete and ineffective in the absence of accountability. Accountability is indispensably required for effective discharge of both moral and legal responsibilities. Likewise, accountability considers in more substantive terms what roles, responsibilities and behavioural rules constitute accountability relationships. Hence, accountability can exit only if there are corresponding responsibilities (moral and legal) that are recognised. For these reasons, responsibility and accountability are mutually connected for effective discharge of functions. In the following section, the nexus between responsibility and accountability is used to derive the intrinsically obligatory nature of CSR along with the need for appropriate CSR regulation for corporate accountability.

CSR, accountability and regulation

Over the last several decades, CSR has mainly been considered as a moral and normative responsibility that corporates can voluntarily pursue. However, more recently there are calls for bringing legal backing for CSR (Kara, 2018; Okoye, 2016; Rahim, 2013). These include scholarly attempts to examine the role of tort law, private law and international law for CSR and corporate accountability (Amao, 2013; Beckers, 2019; Rühmkorf, 2015; Van Calster, 2016; Zerk, 2006) along with formal CSR legislations in several countries around the world. In this context, this paper suggests that considering CSR a moral responsibility has given it a wide scope and attempts to enforce it through legal backing for corporate accountability are not being effective because of this wide scope accorded to CSR (Amodu, 2017). By recasting CSR as consisting of those moral responsibilities that arise in the process of discharging corporates’ legal responsibilities, the paper offers a new approach to linking CSR with moral responsibility and legal responsibility for corporate accountability. The literature has so far investigated whether, why, and how CSR should be regulated. As McInerney (2007) suggests, “Empowering domestic regulators is an essential component of the struggle to realize the positive benefits of capitalist development while limiting its negative effects.” This paper goes beyond the questions of whether, why and how CSR should be regulated to examine what social responsibilities of corporates’ need to be regulated. Thus, in addition to providing an analytical foundation for CSR regulation, the paper identifies corporates’ social responsibilities that have to be regulated by attempting to answer the what question. In the process, the paper defines the boundaries of CSR to provide a basis for CSR regulation.

This paper develops two essential grounds for linking corporate social responsibility to accountability, through functional roles and impacts of businesses. The first is ‘business relation’ and the second is ‘impact relation’. Business relation arises as conducting business is possible only when companies can have required resources, customers, employees and others who are a part of the society or the community where the business operates. Firms have direct relation with these stakeholders to carry on the business functions. This compels them to be responsible towards stakeholders involved in their business operations. Business relation involves obligations that embody those standards, norms, expectations that reflect a concern for what consumers, employees, shareholders, and community regard as fair and just. These are the first set of moral obligations that are associated with the primary functions of business.

The ‘impact relation’ explains the relation between business operations and the potential impacts that they can make. A number of cases illustrate the negative impacts that corporates have on society. The BHRRC in its annual briefing in 2017 tracked 450 cases on human rights abuses by corporates (BHRC, 2017). Such impacts are ongoing especially in developing countries that offer a provision for transnationals to operate their business activities while having weak corporate accountability laws. This paves way for corporates taking undue advantage of weak governance systems resulting in a trade-off between honouring rights and profit making. Their actions may not be illegal in the jurisdictions they operate but may endanger the rights of others. Developing country sweatshops in supply chains are typical examples of this issue. Although their activities are not illegal with the local laws per se, they negatively impact the rights of others while benefiting TNCs by reducing their cost of production to maximise profit. Likewise, corporate generation of harmful environmental externalities is an unsurprising result of wealth maximization model (Susson, 2012). Thus, there are distinct calls for moral responsibility of business entities for the impacts of their business operations.

The case against Shell operations is a classic example to understand the negative impacts that corporates have on the rights of others while maximising their profits (Aurora & Helen, 2011). According to the 2009 Amnesty International report, ‘Shell in the Niger Delta had brought human rights abuses, conflict, impoverishment and despair to a majority of people in the oil producing area’ (Aurora & Helen, 2011). The report noted that ‘decades of pollution and environment damage caused by Multinational Corporations (MNCs) in the oil sector have led to violations of rights to adequate standards of living, rights to food and water, rights to gain a living through work and rights to health’ (Aurora & Helen, 2011). Years of litigation made Shell accountable by compelling it to recognise the moral responsibility of business for their ‘impact relation’. The impact relation, as part of the firm’s moral responsibility, necessitates their responsibility to refrain from causing such impacts and unduly benefit. These impact related obligations are a second set of moral obligations that are associated with the primary functions of business.

As Dillard (2013) suggests, the “ethics of accountability” and “ethics of human rights accountability” demonstrate corporate obligations. According to this view, society and corporates have respective and interdependent rights and duties towards each other for being part of the society and for their constant interactions with each other. The duty that corporates have is fiduciary and this ethical obligation binds corporates with regard to social responsibility and business human rights (Dillard, 2013). They have a responsibility in relation to injustice (Young, 2006) and such unjustified enrichment by violations that cause harm to the rights of others. As one example, advertisement of a cosmetic product may have several negative externalities. Making the right disclosures and providing accurate instructions are corporate obligations towards the consumers. This involves their business relation. Along with these, the firm has an obligation to ensure it does not cause environmental damage while manufacturing the product. This involves their impact relation. While legal responsibility requires firms to conduct the business in consistency with local laws, moral responsibility requires them to meet the obligations of business relation and impact relation. CSR is directly related to this moral responsibility through business relation and impact relation.Footnote 3

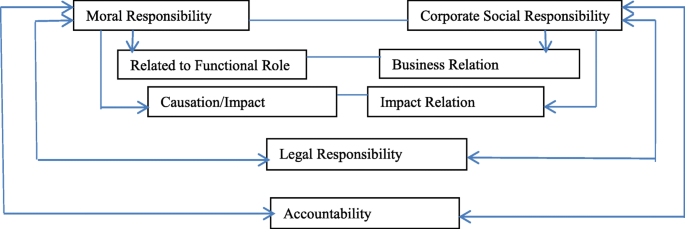

Figure 3 demonstrates the core character of CSR. It represents its link to moral obligations that are associated with legal responsibilities for its functional role and potential impacts. It demonstrates the nexus of such obligations with accountability. The left side of Fig. 3 shows the links between responsibility and accountability. As discussed earlier, moral responsibility is related to the functional role as well as to the causation of impacts when discharging the primary functions under legal responsibility, and through these, to accountability. As self-regulation may not always be realised and tort law may not be adequately developed, Fig. 3 suggests that regulation is essential to ensure accountability in case of moral responsibility. The right side of Fig. 3 shows the corresponding links between CSR and corporate accountability using a parallel model. Using business relation and impact relation in the case of corporations, the framework suggests that regulation is essential to ensure accountability and effective delivery of CSR. Thus, Fig. 3 demonstrates that CSR should be regulated for an effective discharge of corporates’ bundle of obligations by drawing a parallel with the responsibility-accountability presented in Fig. 2.

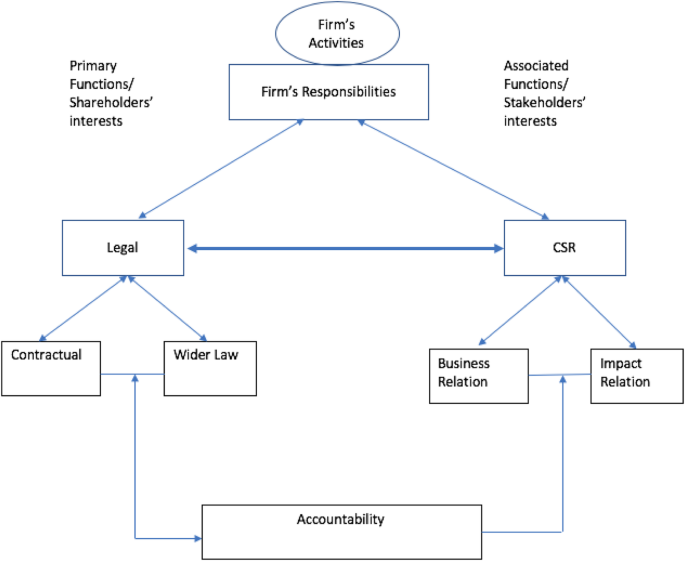

Figure 4 presents an integrated framework for CSR regulation. Firm’s activities are associated with a bundle of responsibilities. On the left side are the legal responsibilities that arise when the firm discharges its primary functions. These include the economic responsibilities of running the firm. On the right side are the moral responsibilities that concurrently arise with these legal responsibilities. This paper suggests that the remit of CSR should be within this set of moral responsibilities. As these are tightly coupled with the legal responsibilities that are enforced through accountability, accountability has to exist for CSR in order to ensure the fulfilment of the responsibilities on the right side of Fig. 4. Thus, any regulation should be targeted to the fulfilment of these moral responsibilities that are concurrently arising with the legal responsibilities associated with the discharge of the primary functions by the firm. Such CSR regulation will be optimal because it will ensure that these moral responsibilities that involve business relation and impact relation are fulfilled, and their fulfilment is prioritised by law as mandatory.

A Framework for CSR Regulation. The figure presents a new framework for CSR regulation by a. identifying the boundaries of CSR as those moral responsibilities that are intertwined with the legal responsibilities associated with the discharge of primary functions by a firm. Such legal responsibilities are defined here to include economic responsibilities such as pursuit of profit. b. demonstrating that accountability is connected with such CSR that arises in the form of business relation and impact relation as developed in the paper c. requiring regulation to ensure that such CSR is mandatorily discharged

Responsibilities under CSR are associated with its business and impact relations that follow from the primary functions of the business. Together they form a bundle of obligations of corporations for effective discharge of corporate functions. These are core obligations that businesses have to abide and adopt in their business practices. The social contract theory (Donaldson, 1982) complements the ‘business relation’ obligations of businesses towards society. The theory suggests an interdependence between business and stakeholders that necessitates ethical obligations towards society. As businesses use resources that a given society provides, they are obliged to give back to that society as their moral obligation. Giving back to the society is a moral obligation that results from social contracts. However, the social contract theory overlooks the fact that these obligations are related to the business relations as such obligations arising from the very existence of business are dependant on the existence of its business relation. Although social contract theorists have rightly suggested that the business have an obligation towards society, they have not considered the fundamental aspect of business relation to the primary functions of business. Furthermore, impact relation emerges as a consequence of business activities when firms are pursuing their primary functions, and firms have obligations to ensure they do not cause harm while pursuing their primary functions.

For these reasons, CSR consisting of both business relation and impact relation are closely linked with the corporates’ legal responsibilities and, as a consequence, their fulfilment is dependent on accountability. As one example, the duty of an accountant in an accounting firm is to maintain the records of the finances of the firm. The duty implores her to maintain fair accounts and calculations, report of any misleading transactions, conflicting interests among others. In case of a breach of such duty, the accountant is answerable for her actions. However, unless there is provision for accountability, it is difficult to take any action against her or to make her liable. Particularly, in the absence of accountability, it is difficult to assess who, to what, to whom and to what extent she is liable. Holding someone accountable for breaching responsibility is important as it acts as a deterrent and compels others to act legally and morally. The framework in Fig. 4 suggests that corporate accountability is essential for the fulfilment of obligations of business relation and impact relation of businesses that form their CSR.

Corporates are needed to proactively engage in CSR practices than considering their business relation as optional or curing the adverse effects of ignoring their impact relation. Such responsibility is in relation to the injustice that may arise as a consequence of their actions and, hence, CSR is closely connected to accountability towards their stakeholders. As discussed here, for this accountability to materialise, regulation is essential as firms may not fulfil their moral responsibilities in its absence. For these reasons, a systematic approach towards meaningful CSR can be achieved by linking it with corporate accountability through regulation.

The framework presented here accomplishes two goals. Firstly, it draws boundaries on what should ideally constitute CSR. The ambiguity in the CSR scholarship with regard to its nature has significantly inhibited the scope for CSR regulation and enforcing corporate accountability for irresponsible activities. By construing CSR as a bundle of moral responsibilities that concurrently arise when discharging legal responsibilities associated the primary functions of the firm, this paper constructs clear boundaries for CSR. This approach to CSR limits the scope of window dressing and other forms of pretentious CSR activities that corporates may design for strategic reasons (or for evading their moral responsibilities that are closely linked to their activities). Secondly, it provides a framework for developing optimal CSR regulation that prioritises moral responsibilities that arise concurrently with legal responsibilities while discharging the primary functions and holds corporates accountable for them. Thus, the paper offers a novel approach that underscores the obligatory nature of CSR, the need for regulation, and a solid basis for developing CSR regulation.

Conclusion

Companies have responsibilities towards society, particular in the context of their business location and activities. To a large extent, CSR has remained a corporate strategy tool that does not impose mandatory obligations on corporates. In the absence of accountability through direct regulation, this vast literature on corporate social responsibility has wrongly assumed voluntarism and diluted the obligations that are otherwise unavoidable in nature. Furthermore, unstandardized terms of corporate accountability have encouraged businesses to pursue CSR while disregarding or completely evading accountability.

The theoretical foundation developed here suggests that CSR is a mandatory obligation and not an optional voluntary provision for corporates as it is closely related to the primary functions of businesses. It has direct link to the legal obligations and accountability. Regulation is pre-requisite for effective discharge of the bundle of obligations of businesses for corporate accountability without which both legal and moral responsibilities have weak foundations. Corporates’ moral responsibility through business relation and impact relation as developed here strengthens the argument that CSR is an obligation towards society through its relation to the primary functions of the business that are mandated upon the corporates.

The paper discusses the intrinsic connection between responsibility and accountability as a natural foundation for the nexus between CSR and corporate accountability. This paper sets out to develop a formal structure by linking responsibility with accountability. The CSR regulation framework developed here links obligations under CSR with legal responsibilities of business. It suggests that social obligations and economic goals are akin to moral and legal responsibilities that are intrinsically linked to each other. As firms are unlikely to fulfil these responsibilities in the absence of accountability, the paper proposes a novel theoretical foundation linking responsibility with accountability as a basis for regulating CSR. The responsibilities under the CSR must be seen as the moral responsibilities that are related to the functional role of businesses and to the potential impacts that businesses can have. The concept of CSR developed here, as an indispensable moral obligation rooted in business relation and impact relation, provides a clear grounding for regulating CSR. This identifies the microfoundations of responsibility, and demonstrates that accountability through regulation is essential for fulfilling moral obligations.

In summary, this article makes several compelling contributions to the scholarship on ethics and CSR. It provides a foundation for developing a framework of social obligations regarding what, to whom, and the extent of responsibilities while underscoring the role of obligations in proactively engaging business in socially benefitting duties in addition to refraining them from activities that cause harm to the society. Furthermore, it suggests that the legal and moral responsibilities should be taken together as the bundle of obligations of businesses to effectively discharge their functions with accountability inevitably linked to moral responsibility, thus, underscoring the need for regulating CSR for accountability. Furthermore, the paper provides a compelling new approach towards CSR by identifying it with immediate moral obligations that arise through business relation and impact relation while discharging the primary functions and the associated legal responsibilities. Through this, the paper constructs boundaries for CSR and enables the development of an effective regulatory regime for CSR around the world.

Availability of data and materials

Not Applicable.

Notes

Section 135, Companies Act 2013, Government of India

Throughout this paper, regulation is legal regulation unless specified otherwise.

Such moral responsibilities include protecting the interests of stakeholders (Laplume, Sonpar, & Litz, 2008), preventing adverse impacts on environment, or having consideration for the health and safety of employees among others.

Abbreviations

- BHRRC:

-

Business and Human Rights Resource Centre

- CSR:

-

Corporate Social Responsibility

- GRI :

-

Global Reporting Initiatives

- MNCs:

-

Multinational Corporations

- OECD:

-

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- TBL:

-

Triple Bottom Line

- TNCs:

-

Transnational Corporations

References

Aaronson, S. (2005). “Minding our business”: what the United States government has done and can do to ensure that U.S. multinationals act responsibly in foreign markets. Journal of Business Ethics, 59, 175–198.

Abah, A. L. (2016). Legal regulation of CSR: the case of social media and gender-based harassment. University of Baltimore Journal of Media Law & Ethics, 5, 38.

Adams, C. A. (2004). The ethical, social and environment reporting-performance portrayal gap. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 17(5), 731–757.

Adams, C., Frost, G., & Webber, W. (2004). Triple bottom line: A review of the literature. In Adrian Henriques and Julie Richardson (Eds.), The Triple Bottom Line: Does It All Add Up (pp. 17–25). Routledge.

Agudelo, M. A. L., Jóhannsdóttir, L., & Davídsdóttir, B. (2019). A literature review of the history and evolution of corporate social responsibility. International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility, 4(1), 1.

Aguinis, H. (2011). Organizational responsibility: doing good and doing well. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 3, pp. 855–879). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Aguinis, H., & Glavas, A. (2012). What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 38(4), 932–968.

Alamgir, F., & Banerjee, S. B. (2019). Contested compliance regimes in global production networks: Insights from the Bangladesh garment industry. Human Relations; Studies Towards the Integration of the Social Sciences, 72(2), 272–297.

Alves, I. M. (2009). Green spin everywhere: how green washing reveals the limits of the CSR paradigm. Journal of Global Change & Governance, 2(1), 1–26.

Amao, O. (2013). Corporate social responsibility, human rights and the law: multinational corporations in developing countries. Abingdon: Routledge.

Amodu, N. (2017). Regulation and enforcement of corporate social responsibility in corporate Nigeria. Journal of African Law, 61(1), 105–130.

Aurora, V., & Helen, Y. (2011). The business of human rights: an evolving agenda for corporate responsibility. London: Zed Books Ltd.

Baden, D. (2016). A reconstruction of Carroll’s pyramid of corporate social responsibility for the 21st century. International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility, 1(1), 8.

Barnett, M. L. (2016). The business case for corporate social responsibility: A critique and an indirect path forward. Business & Society, 58(1), 167–190.

Barrett, W. (2004). Responsibility, Accountability and Corporate Activity, Opinion: Australia’s E-journal of Social and Political Debate. Available at https://www.onlineopinion.com.au/view.asp?article=2480.

Barry, V., & Shaw, W. H. (1979). Moral issues in business. Belmont: Wadsworth.

Beckers, A. (2019). Towards a regulatory private law approach for CSR self-regulation? The effect of private law on corporate CSR strategies. European Review of Private Law, 27(2), 221–243.

Berliner, D., & Prakash, A. (2012). From norms to programs: The United Nations global compact and global governance. Regulation & Governance, 6(2), 149–166.

BHRC (2017). “Corporate impunity is common & remedy for victims is rare”. Business and human rights resource center. Available at: https://www.business-humanrights.org/sites/default/files/documents/CLA_AB_Final_Apr%202017.pdf. Accessed on 4 Aug 2019.

Bivins, T. (2006). Responsibility and accountability. In K. Fitzpatrick & C. Bronstein (Eds.), Ethics in Public Relations: Responsible Advocacy, 19–38. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Bondy, K., Matten, D., & Moon, J. (2008). Multinational corporation codes of conduct: Governance tools for corporate social responsibility? Corporate Governance: An International Review, 16(4), 294–311.

Bowen, H. R., & Johnson, F. E. (1953). Social responsibility of the businessman. New York: Harper.

Buhmann, K. (2006). Corporate social responsibility: What role for law? Some aspects of law and CSR. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 6(2), 188–202.

Buhmann, K. (2011). Integrating human rights in emerging regulation of corporate social responsibility: The EU case. International Journal of Law in Context, 7(2), 139–179.

Carroll, A. B. (1979). A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. The Academy of Management Review, 4(4), 497–505.

Carroll, A. B. (1991). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons, 34(4), 39–48.

Carroll, A. B. (1999). Corporate social responsibility: evolution of a definitional construct. Business & Society, 38(3), 268–295.

Carroll, A.B., & Shabana, K.M. (2010). The Business Case for Corporate Social Responsibility: A review of concepts, research and Practice. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12(1), 85–105.

Carroll, A. B. (2016). Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: taking another look. International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility, 1(1), 3.

Chauvey, J. N., Giordano-Spring, S., Cho, C. H., & Patten, D. M. (2015). The normativity and legitimacy of CSR disclosure: evidence from France. Journal of Business Ethics, 130(4), 789–803.

Chhaparia, P., & Jha, M. (2018). Corporate social responsibility in India: the legal evolution of CSR policy. Amity Global Business Review, 13(1), 79–84.

Dahlsrud, A. (2008). How corporate social responsibility is defined: an analysis of 37 definitions. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 15(1), 1–13.

Davis, K. (1960). Can business afford to ignore social responsibilities? California Management Review, 2(3), 70–76.

Davis, K. (1973). The case for and against business assumption of social responsibilities. The Academy of Management Journal, 16(2), 312–322.

Demirbag, M., Wood, G., Makhmadshoev, D., & Rymkevich, O. (2017). Varieties of CSR: institutions and socially responsible behaviour. International Business Review, 26(6), 1064–1074.

Dentchev, N. A., Haezendonck, E., & van Balen, M. (2017). The role of governments in the business and society debate. Business & Society, 56(4), 527–544.

Dentchev, N. A., van Balen, M., & Haezendonck, E. (2015). On voluntarism and the role of governments in CSR: towards a contingency approach. Business Ethics: A European Review, 24(4), 378–397.

Devlin, P. (1965). The enforcement of morals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dhiman, A., Sen, A., & Bhardwaj, P. (2018). Effect of self-accountability on self-regulatory behaviour: A quasi-experiment. Journal of Business Ethics, 148(1), 79–97.

Dillard, J. (2013). Human rights within an ethic of accountability. In: Corporate social responsibility (Vol. 196(220)196-220). Routledge in association with GSE Research.

Donaldson, T. (1982). Corporations and morality. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Drucker, P. F. (1984). Converting social problems into business opportunities: The new meaning of corporate social responsibility. California Management Review, 26(000002), 53.

Dworkin, G. (1998). Devlin was right: Law and the enforcement of morality. William and Mary Law Review, 40, 927.

Dworkin, R. (1966). Lord Devlin and the enforcement of morals. The Yale Law Journal, 75(6), 986–1005.

Eabrasu, M. (2012). A moral pluralist perspective on corporate social responsibility: From good to controversial practices. Journal of Business Ethics, 110(4), 429–439.

Eccles, R. G., & Krzus, M. P. (2010). One report: integrated reporting for a sustainable strategy. Hoboken: Wiley.

Eccles, R. G., & Krzus, M. P. (2014). The integrated reporting movement: meaning, momentum, motives, and materiality. Hoboken: Wiley.

Eccles, R. G., Krzus, M. P., & Ribot, S. (2015). Meaning and momentum in the integrated reporting movement. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 27(2), 8–17.

Eccles, Robert G. and Krzus, Michael P. and Solano, Carlos (2019). A comparative analysis of integrated reporting in ten countries. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3345590 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3345590.

Elkington, J. (1994). Towards the sustainable corporation: win-win-win business strategies for sustainable development. California Management Review, 36(2), 90–100.

Elkington, J. (1997). Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st century business. Oxford: Capstone Publishing.

Elkington, J. (1998a). Accounting for the triple bottom line. Measuring Business Excellence, 2(3), 18–22.

Elkington, J. (1998b). Partnerships from cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st-century business. Environmental Quality Management, 8(1), 37–51.

Elkington, J. (2018). 25 years ago I coined the phrase “triple bottom line.” Here’s why it’s time to rethink it. Harvard Business Review, 25. Available at https://hbr.org/2018/06/25-years-ago-i-coined-the-phrase-triple-bottom-line-heres-why-im-giving-up-on-it.

Freeman, I., & Hasnaoui, A. (2011). The meaning of corporate social responsibility: The vision of four nations. Journal of Business Ethics, 100(3), 419–443.

Freeman, R.E. (1984). Strategic management: a stakeholder approach. Pitman: Boston.

Freeman, R. E. (2010). Strategic management: a stakeholder approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Friedman, M. (1970). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. New York: New York Times Magazine.

Frink, D. D., & Klimoski, R. J. (1998). Towards a Theory of Accountability in organisations and human resource management. In G. R. Ferris (Ed.), Research in personnel and human resource management (Vol. 16, pp. 1–51). Stamford: JAI Press.

Gatti, L., Vishwanath, B., Seele, P., & Cottier, B. (2019). Are we moving beyond voluntary CSR? Exploring theoretical and managerial implications of mandatory CSR resulting from the New Indian Companies Act. Journal of Business Ethics, 160(4), 961–972.

Goldberg, J. C., & Zipursky, B. C. (2006). Tort law and moral luck. Cornell Law Review, 92, 1123.

Green, L. (2008). Positivism and the inseparability of law and morals. New York University Law Review, 83, 1035.

Idemudia, U., & Kwakyewah, C. (2018). Analysis of the Canadian national corporate social responsibility strategy: Insights and implications. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 25(5), 928–938.

IIRC (2013). Integrated reporting, international integrated reporting council. Available at: https://integratedreporting.org/resource/international-ir-framework/.

Jamali, D., Lund-Thomsen, P., & Khara, N. (2017). CSR institutionalized myths in developing countries: An imminent threat of selective decoupling. Business & Society, 56(3), 454–486.

Jansen, N. (2013). The idea of legal responsibility. Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, 34(2), 221–252.

Jenkins, R. (2005). Globalization, corporate social responsibility and poverty. International Affairs, 81(3), 525–540.

Kara, P. (2018). The role of corporate social responsibility in corporate accountability of multinationals: is it ever enough without ‘hard law’? European Company Law, 15(4), 118–125.

Keith, N. (2010). Evolution of corporate accountability: From moral panic to corporate social responsibility. Business Law International, 11, 247.

Knudsen, J. S. (2018). Government regulation of international corporate social responsibility in the US and the UK: how domestic institutions shape mandatory and supportive initiatives. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 56(1), 164–188.

Lamarche, T., & Bodet, C. (2018). Does CSR contribute to sustainable development? What a regulation approach can tell us. Review of Radical Political Economics, 50(1), 154–172.

Laplume, A. O., Sonpar, K., & Litz, R. A. (2008). Stakeholder theory: reviewing a theory that moves us. Journal of Management, 34(6), 1152–1189.

Lee, M. D. P. (2008). A review of the theories of corporate social responsibility: its evolutionary path and the road ahead. International Journal of Management Reviews, 10(1), 53–73.

Leonidou, C. N., & Skarmeas, D. (2017). Gray shades of green: Causes and consequences of green skepticism. Journal of Business Ethics, 144(2), 401–415.

Levitt, T. (1958). The dangers of social-responsibility. Harvard Business Review, 36, 41.

Luo, J., Kaul, A., & Seo, H. (2018). Winning us with trifles: adverse selection in the use of philanthropy as insurance. Strategic Management Journal, 39(10), 2591–2617.

Macdonald, K. (2014). The meaning and purposes of transnational accountability. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 73(4), 426–436.

Malesky, E., & Taussig, M. (2017). The danger of not listening to firms: government responsiveness and the goal of regulatory compliance. The Academy of Management Journal, 60(5), 1741–1770.

Malesky, E., & Taussig, M. (2019). Participation, government legitimacy, and regulatory compliance in emerging economies: a firm-level field experiment in Vietnam. American Political Science Review, 113(2), 530–551.

Matten, D., & Moon, J. (2008). “Implicit” and “explicit” CSR: a conceptual framework for a comparative understanding of corporate social responsibility. The Academy of Management Review, 33(2), 404–424.

McInerney, T. (2007). Putting regulation before responsibility: towards binding norms of corporate social responsibility. Cornell International Law Journal, 40, 171.

McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. (2001). Corporate social responsibility: a theory of the firm perspective. The Academy of Management Review, 26(1), 117–127.

Meynhardt, T., & Gomez, P. (2019). Building blocks for alternative four-dimensional pyramids of corporate social responsibilities. Business & Society, 58(2), 404–438.

Nieto, P. (2005). Why regulating: corporate social responsibility is a conceptual error and implies a dead weight for competitiveness. Tanpa Tahun: The European Enterprise Journal.

Norman, W., & MacDonald, C. (2004). Getting to the bottom of “triple bottom line”. Business Ethics Quarterly, 14(2), 243–262.

Okoye, A. (2009). Theorising corporate social responsibility as an essentially contested concept: is a definition necessary? Journal of Business Ethics, 89(4), 613–627.

Okoye, A. (2016). Legal approaches and corporate social responsibility: towards a Llewellyn’s law-jobs approach. Abingdon: Routledge.

Osuji, O. (2011). Fluidity of regulation-CSR nexus: the multinational corporate corruption example. Journal of Business Ethics, 103(1), 31–57.

Osuji, O. K. (2015). Corporate social responsibility, juridification and globalisation:‘inventive interventionism’for a ‘paradox’. International Journal of Law in Context, 11(3), 265–298.

Panda, S., D'Souza, D. E., & Blankson, C. (2019). Corporate social responsibility in emerging economies: investigating firm behavior in the Indian context. Thunderbird International Business Review, 61(2), 267–276.

Parsa, S., Roper, I., Muller-Camen, M., & Szigetvari, E. (2018). Have labour practices and human rights disclosures enhanced corporate accountability? The case of the GRI framework. In: Accounting forum (Vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 47-64). Taylor & Francis.

Rahim, M. M. (2013). Legal regulation of corporate social responsibility. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-40400-9.

Rivera, H. F. (2013). Business and human rights: towards an effective legal regulation, or the maintenance of the status quo? Mexican Yearbook of International Law, 13, 313–354.

Ross, D. (2017). A research-informed model for corporate social responsibility: towards accountability to impacted stakeholders. International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility, 2(1), 8.

Rühmkorf, A. (2015). Corporate social responsibility, private law and global supply chains. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Sachs, S., Rühli, E., & Kern, I. (2009). Sustainable success with stakeholders: the untapped potential. Berlin: Springer.

Schembera, S. (2018). Implementing corporate social responsibility: empirical insights on the impact of the UN global compact on its business participants. Business & Society, 57(5), 783–825.

Schrempf-Stirling, J., & Wettstein, F. (2017). Beyond guilty verdicts: human rights litigation and its impact on corporations’ human rights policies. Journal of Business Ethics, 145(3), 545–562.

Shiu, Y. M., & Yang, S. L. (2017). Does engagement in corporate social responsibility provide strategic insurance-like effects? Strategic Management Journal, 38(2), 455–470.

Singh, S., Holvoet, N., & Pandey, V. (2018). Bridging sustainability and corporate social responsibility: culture of monitoring and evaluation of CSR initiatives in India. Sustainability, 10(7), 2353.

Situ, H., Tilt, C. A., & Seet, P. S. (2018). The influence of the government on corporate environmental reporting in China: an authoritarian capitalism perspective. Business & Society, 0007650318789694.

Sobczak, A. (2006). Are codes of conduct in global supply chains really voluntary? From soft law regulation of labour relations to consumer law. Business Ethics Quarterly, 16(2), 167–184.

Subramaniam, N., Kansal, M., & Babu, S. (2017). Governance of mandated corporate social responsibility: evidence from Indian government-owned firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 143(3), 543–563.

Susson, M. A. (2012). Environments, externalities and ethics: compulsory multinational and transnational corporate bonding to promote accountability for externalization of environmental harm. Buffalo Environmental Law Journal, 20, 65.

Szabó, D. G., & Sørensen, K. E. (2015). New EU directive on the disclosure of non-financial information (CSR). Nordic & European Company Law Working Paper, (15-01).

Thirarungrueang, K. (2013). Rethinking CSR in Australia: time for binding regulation? International Journal of Law and Management, 55(3), 173–200.

Van Calster, G. (2016). European private international law. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Vigneau, L., Humphreys, M., & Moon, J. (2015). How do firms comply with international sustainability standards? Processes and consequences of adopting the global reporting initiative. Journal of Business Ethics, 131(2), 469–486.

Visser, W. (2006). Revisiting Carroll’s CSR pyramid. Corporate citizenship in developing countries, 29–5e6.

Vos, J. (2009). Actions speak louder than words: greenwashing in corporate America. Notre Dame Journal of Law Ethics & Public Policy, 23, 673.

Waddock, S. (2004). Parallel universes: Companies, academics, and the progress of corporate citizenship. Business & Society Review, 109(1), 5–42.

Wood, D. J. (2010). Measuring corporate social performance: a review. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12(1), 50–84.

Wright, C., & Nyberg, D. (2017). An inconvenient truth: how organizations translate climate change into business as usual. The Academy of Management Journal, 60(5), 1633–1661.

Young, I. M. (2006). Responsibility and global justice: a social connection model. Social Philosophy and Policy, 23(1), 102–130.

Zerk, J. A. (2006). Multinationals and corporate social responsibility: limitations and opportunities in international law (Vol. 48). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zuo, W., Schwartz, M. S., & Wu, Y. (2017). Institutional forces affecting corporate social responsibility behavior of the Chinese food industry. Business & Society, 56(5), 705–737.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the editor Samuel Idowu, two anonymous referees, and Onyeka Osuji for their constructive suggestions. An earlier draft of the paper was awarded the best paper award at the Erasmus Early-Career Scholars Conference 'New business models and globalised markets: Rethinking public and private responsibilities' at Erasmus University in 2018. The author thanks the participants at this Conference and at a Essex Law School Seminar for their comments.

Funding

Not Applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

One Author.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Not Applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Tamvada, M. Corporate social responsibility and accountability: a new theoretical foundation for regulating CSR. Int J Corporate Soc Responsibility 5, 2 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40991-019-0045-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40991-019-0045-8